Wonderful podcast interview with WCCO’s Jordana Green and award-winning columnist and speaker Caryn Sullivan about the anthology Here in the Middle: Stories of Love, Loss and Connection from the Ones Sandwiched in between!

Source: Jordana Green

Wonderful podcast interview with WCCO’s Jordana Green and award-winning columnist and speaker Caryn Sullivan about the anthology Here in the Middle: Stories of Love, Loss and Connection from the Ones Sandwiched in between!

Source: Jordana Green

Last night, I was offered an extraordinary opportunity to do something I, a formerly rural, small-town, Methodist-turned-Catholic girl, would never have thought I’d do: I sat in the women’s section of my local mosque and watched as the women engaged in their final prayer session of the night.

Last night, I was offered an extraordinary opportunity to do something I, a formerly rural, small-town, Methodist-turned-Catholic girl, would never have thought I’d do: I sat in the women’s section of my local mosque and watched as the women engaged in their final prayer session of the night.

This unexpected gift came about thanks to a community forum I attended entitled “How to Oppose Hate,” sponsored by our local Maryland State Delegate Eric Luedtke, our local Muslim Community Center, the Association of Black Democrats of Montgomery County, CASA de Maryland (a local nonprofit serving low-income immigrant communities), the Muslim Democratic Club of Montgomery County, Maryland State Senator Craig Zucker, Maryland Delegate Anne Kaiser, and Maryland Delegate Pam Queen.

Aside from the obvious appeal of the topic, the diversity of the speaker panel is what interested me most; it included Imam Mohamed Abdullahi, Rabbi Ari Sunshine, Reverend Mansfield Kaseman, and community leaders Gabriel Acevero, Hamza Khan, and Delegate Eric Luedtke.

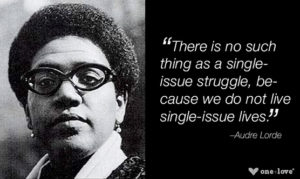

The panel proceeded much as one would expect, with a moderator posing a set of five prepared questions and passing the mic from speaker to speaker, giving each the opportunity to respond. There were many moments of great profundity in their thoughtful, heartfelt replies; below is a sample of what they had to say. With one notable exception involving a speaker using a quote from Audre Lord, which I’m including, I am deliberately not providing individual attributions for these words, because I sensed throughout the evening that these individuals were united in the hope of speaking with one voice:

The panel proceeded much as one would expect, with a moderator posing a set of five prepared questions and passing the mic from speaker to speaker, giving each the opportunity to respond. There were many moments of great profundity in their thoughtful, heartfelt replies; below is a sample of what they had to say. With one notable exception involving a speaker using a quote from Audre Lord, which I’m including, I am deliberately not providing individual attributions for these words, because I sensed throughout the evening that these individuals were united in the hope of speaking with one voice:

In all honesty, that last sentence about ignorance–and its polar opposite, curiosity–is what drew me to the forum last night. I have spent nearly four years now, driving past the Muslim Community Center, without ever going in, and judging from comments by other attendees, I was not alone. The MCC sits smack in the middle of a long stretch of numerous faith communities, so many concentrated in this one area, in fact, that Delegate Luedtke referred to the street as the “Highway to Heaven.”

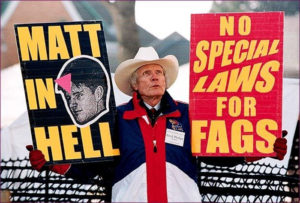

There has been so much media coverage about the administration’s recent attempt at a Muslim travel “ban,” that the plight of the Muslim community has been weighing heavily on my mind. Before anyone gets their undies in a bunch, puffing out their chests with “What about the illegal immigrants’ plight? What about the women’s plight? What about the scourge of anti-Semitism? What about etc., etc., etc.?” Please, refer to the third bullet above.

So–when I saw that the community forum would be held at the Muslim Community Center, with an actual imam on the panel, I knew I wanted to hear what the panel would say.

So how did I, then, wind up watching a prayer service later that evening? Simple: The imam extended a gracious, loving invitation to all those present, and I, curious, accepted. Ignorance may be the enemy, but curiosity is its greatest foe.

But now, I must engage in a little truth-telling, in the vein of that second bullet above, the one about difficult conversations. I learned a lot about myself during my evening at the mosque, and it’s not all stuff I was happy to learn. It’s not ever easy to learn awful truths about yourself, but sometimes, those most difficult conversations are precisely the ones you need the most.

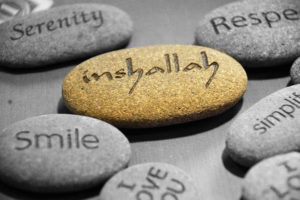

diverse—in Arabic, and I heard “inshallah,” I was, I’ll admit, unnerved for a moment. Let me repeat that: A faith leader using a phrase that translates into “God willing” unnerved me. Why? Because it was said in Arabic. Did I know the phrase as an expression of faith? No. Thanks to our post-9/11 culture, where Muslims have been so successfully demonized as our #1 enemy, the only reason I even recognized the phrase was thanks to movies and TV shows where Muslims are so often depicted as terrorists. Ignorance is the enemy.

diverse—in Arabic, and I heard “inshallah,” I was, I’ll admit, unnerved for a moment. Let me repeat that: A faith leader using a phrase that translates into “God willing” unnerved me. Why? Because it was said in Arabic. Did I know the phrase as an expression of faith? No. Thanks to our post-9/11 culture, where Muslims have been so successfully demonized as our #1 enemy, the only reason I even recognized the phrase was thanks to movies and TV shows where Muslims are so often depicted as terrorists. Ignorance is the enemy. arose, a louder voice of reason, a voice I’ve long worked to strengthen through education, began shouting the other one down: What the hell is the matter with you? What on earth are you afraid of? Open your eyes, ignoramus, look again. I did, and I saw, with deep chagrin, that the men were just hitching up their pants as they prepared to kneel in prayer, saving us all from a mass incident of plumber’s crack. IGNORANCE IS THE ENEMY.

arose, a louder voice of reason, a voice I’ve long worked to strengthen through education, began shouting the other one down: What the hell is the matter with you? What on earth are you afraid of? Open your eyes, ignoramus, look again. I did, and I saw, with deep chagrin, that the men were just hitching up their pants as they prepared to kneel in prayer, saving us all from a mass incident of plumber’s crack. IGNORANCE IS THE ENEMY.

This is the difficult conversation I had with myself last night, and which I share with you, in hopes that it will inspire you to have some of your own. What is holding you back from engaging with others who are different from you? I participated in an extraordinary opportunity last night, offered to me and to all with love and open arms by the Muslim community. It’s easy to consider yourself open-minded and tolerant and accepting because you think you’re saying the right words, or because you can say, “I know some Muslim people, or some blacks, or some gays, or some cops, or some Trump supporters, or some undocumented immigrants, or some refugees, or some women who’ve had abortions.” It’s another thing entirely to examine your own fears and then take the necessary steps to combat them with one of the greatest weapons the human mind possesses—curiosity. Curiosity led me to attend the forum; curiosity ushered me across the threshold; curiosity drew me to witness a faithful, loving, peaceful group of women at prayer, and it changed me.

It was an extraordinary experience, one that perhaps, were we living in less extraordinary times, may not have moved me so deeply. I hope with all my heart that moments like these, where we reach out to engage with and embrace others who, on the surface seem so different, will someday become less extraordinary, become instead ordinary, unremarkable. I hope that someday we will finally understand how much more alike we are than we are different. It starts with each one of us taking that first step. If we do not now have the difficult conversations with ourselves about our own deepest fears, intolerance, and ignorance, how can we ever hope to prevail in the difficult conversations we must now have, as communities and as a nation, with others who are afraid because they are ignorant, uneducated, ill-informed, or, perhaps worst of all, incurious? This important work begins inside each of us, alone.

I urge you to follow your curiosity, to actively begin stepping outside of your comfort zone. Don’t just be a mindless sheep, following only what the media or other people tell you, not even me. Go and see for yourselves, I urge you. It will make all the difference in your perspective. Learn about other faiths, engage with people from other communities, from other backgrounds. Don’t let your fears dictate your behavior. Ask questions, show up, be a part of their world, and invite them to be part of yours–because really, it’s never been about “my world” and “their world.” It’s always been “our world.”

This post is part of the Candlesticks and Daggers Interview Series run by contributor Sati Benes Chock, and originally appeared January 19, 2017, on the blog of Candlesticks and Daggers editor, Kelly Ann Jacobson. For more about the book, please follow the link here.

This post is part of the Candlesticks and Daggers Interview Series run by contributor Sati Benes Chock, and originally appeared January 19, 2017, on the blog of Candlesticks and Daggers editor, Kelly Ann Jacobson. For more about the book, please follow the link here.

Excerpt from Julia Tagliere’s story “His Last Human Day”

Trapped, he crouches, contemplating the giant sludge of applesauce oozing between his toes, and tries to remember exactly when everything went wrong. Then he does remember: He no longer has toes. It’s just another mind trick he still hasn’t conquered, like remembering he has an exoskeleton now, not skin. They say karma’s the bitch, but for him, it’s the remembering.

Interview

Hi Julia! Can you tell us a little about how you became a writer? How did you begin? Did you always know that you wanted to be a writer?

As I suspect is the case with many writers, I started writing very young and wrote a lot of early garbage, resorting to non-writing employment—in my case, nine years of teaching high school Spanish and French—for survival purposes. Actually, when I began college, I really thought I’d be an interpreter at the UN by now; funny how things work out, isn’t it? After my third consecutive maternity leave, I took up writing again to save my sanity, and started taking graduate writing classes to get better at it. Sixteen years later, I’m still working on that.

What do you read for fun?

Anything by Neil Gaiman (I read Good Omens at least once every year) and Cook’s Illustrated magazine—outstanding writing, detailed research, and a healthy dose of dark fantasy (especially the cooking magazine). I’m also doing the Book Riot Read Harder 2017 Challenge this year, which will have me reading things outside of my comfort zone this year; they may not all be “fun,” but we shall see.

Some writers have rituals that they feel helps them with the creative process. Do you employ any rituals, or do anything regularly that helps keep you on track with your writing?

When I’m composing, I burrow into my comfy chair, put my feet up, and work with my laptop propped on a pillow on my legs; I can sit like that for hours without moving. When I’m revising, however, I’m all business—I hunch over my desktop keyboard to work, streaming classical music to help me tune out any distractions. Both approaches are terrible for one’s back; I’m certain later in life I’ll wind up emulating Dalton Trumbo and have to write in my bathtub. Keeping track of my daily word count keeps me honest.

You have a lot of experience with writing programs, having studied at DePaul University and most recently getting your M.A. from Johns Hopkins (Congrats!). What would you say to beginning writers who are trying to decide whether or not to enter a program? Is there anything you’d wished that you’d known before applying?

Dirty little secret time: I don’t believe that, in and of themselves, writing programs make anyone a better writer (except for Ed Perlman’s Sentence Power class—that kicked my butt. Thank you, Ed). In fact, I think that’s a mistake many beginning writers make—believing that if they just complete a program they’ll magically become great writers. What writing programs do, and it’s something I feel both DePaul and Johns Hopkins do quite well, is create opportunities: opportunities, in a (largely) supportive communal setting, to study, to analyze, to reflect, to debate, to connect, to be exposed (and I mean that in dual senses, both to be exposed to other works and viewpoints and such, as well as to be exposed as a writer oneself). Recognizing those opportunities and taking advantage of them with an open mind, a willing spirit, and the tenacity to put in some really hard work—that’s what makes one a better writer. Could you accomplish this growth on your own, outside of a formal writing program? Perhaps, but it’d be far more difficult to recreate such a banquet of opportunities in isolation.

If you could tell beginning writers one thing about the publishing process, what would it be? Any advice for writers trying to crack the anthology market?

We’d all like to think that being published is simply a matter of being talented, but the hard truth is that getting published requires more than just being a good writer. The world is full of good writers. The ones who are published are the ones who put themselves in the right place at the right time, something you do by getting out there and meeting people. I know, we’d all much rather snuggle into our comfy chairs and pretend the world doesn’t exist, but it just doesn’t work that way. Get out there! Attend conferences, seminars, lectures, readings, become active on social media; that is how you make the connections that will get your work seen.

Your story, “His Last Human Day,” was a ton of fun. Without giving away too much of the story, I’d like to talk about it a bit. This is a tale about transformation, on a number of levels. What touched me most about it was how well you humanize a character that is a species most find abhorrent. Was that difficult to do, or did it just sort of happen organically?

One of the things I found so difficult about reading Kafka’s Metamorphosis (and this piece is obviously an homage) was that Samsa was just so gross (I can’t watch the Jeff Goldblum version of The Fly, either). For me, personally, as a reader, the grossness got in the way of the story; I knew that, if I was going to be able to say what I wanted to say with this piece, I would have to tone down the gross-out factor quite a bit, perhaps even incorporate some humor. Once I made that decision, the actual humanization came about rather organically.

How did you come up with the idea for this story, I mean…were you just standing there in the shower, thinking dark thoughts while pondering Kafka….and…suddenly, you weren’t alone? In other words, any basis in real life, or was this just one of those fantasies that evolved out of “what if’s”?

This piece came about in two ways: First, the house we’d just moved into had a huge infestation of stink bugs; those little fuckers were everywhere. As I was showering one morning, I noticed a stink bug on the door; it was just sitting there, swinging its antennae back and forth, looking for all the world like it was actively watching me shower— that left a very disturbing impression. Then, in one of my classes later that week, we did a first-line swap: We each wrote an original first line on the chalkboard and then chose someone else’s line to start a new piece. I chose one about someone standing in a bowl of applesauce and wondering where everything went wrong, but when I began working on the assignment, using a normal-sized human protagonist just didn’t work; for my purposes, the character had to be someone (or something) very small. Of course, I thought immediately of my stinkbug stalker, but I worried about being perceived as ripping off Kafka. After much deliberation, I tackled the problem head-on by making the character an actual cockroach (a common misconception of Samsa’s character) and having the cockroach itself address Kafka’s work directly in the piece. It turned out to be one of the most fun pieces of writing I’ve done to date.

You wrote a novel, Widow Woman, in 2012. One theme of that work was forgiveness, which is also touched upon in “His Last Human Day.” Do you find that this is a recurring theme for your writing?

Yes, it is a recurring theme. I suspect it’s because I have a hard time with cynicism. Perhaps that makes me a Pollyanna or a naïve chump, but I always want to believe the best of others, no matter how abhorrent. Enough evil exists and dark things happen every day in real life; in my fiction, I can let the more optimistic, hopeful side of my imagination take over and create those opportunities for redemption. It’s not always granted, of course—wouldn’t that be dull? But the opportunities are definitely there.

Any future projects (or anything else) you want to tell us about?

I have a few short pieces already in the pipeline, along with an upper middle-grade adventure I’ve finished and am hoping to get out in 2017. As far as new writing, I’ll be working on completing my third novel, The Day the Music Didn’t Die, a fun work of magic realism for adult readers I’m excited to get back to now that I’m done with my classes; I also blog about “stuff” at justscribbling.com.

Julia Tagliere is a freelance writer and editor and studied in the M.A. in Creative Writing program at DePaul University in Illinois. Her work has appeared in magazines such as The Writer and Hay & Forage Grower and in numerous online publications. Julia’s debut novel, Widow Woman, was published in 2012. In 2014, Open to Interpretation, the juried photography and prose series, selected Julia’s short story, “The Navigator,” for publication in Love + Lust, its fourth and final installment. Another of her recent stories, “Te Absolvo,” won Best Short Story in the 2015 William Faulkner Literary Competition. This December, her personal essay, “Stars I Will Find,” appears in a collection of stories about the challenges of simultaneously caring for growing children and aging parents, Here In The Middle: Stories Of Love, Loss, And Connection From The Ones Sandwiched In Between. An active blogger and past finalist in Minneapolis’ Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series Competition, Julia resides in Maryland with her family, where she recently completed her M.A. in Fiction Writing at Johns Hopkins University.

It’s been a couple of days now, and I’ve given the Women’s March a lot of thought. I called this photo album “Julia’s March,” because I want to be clear that the photos in it represent what I saw that day, what I felt that day, and what I hoped that day would bring about. So here are my thoughts:

It’s been a couple of days now, and I’ve given the Women’s March a lot of thought. I called this photo album “Julia’s March,” because I want to be clear that the photos in it represent what I saw that day, what I felt that day, and what I hoped that day would bring about. So here are my thoughts:

1. In this era of fake news, it’s critical for us to stop relying on biased media. Fox, CNN, MSNBC, Breitbart, ABC, NBC–they ALL have slants, they all have agendas. It’s time for us to see with our own eyes, hear with our own ears, and make better informed judgments. With that in mind, I didn’t caption most of these photos, because I want you to look at what I saw and make your own judgments. Please, however, pay close attention to the faces of the people in them. Notice the genders, notice the ages, notice the colors, notice the expressions, notice what the signs say, whether you like them or not.

2. I don’t consider myself a feminist. I consider myself a wife, a mother, a woman, a human being. The only one of those I marched to fight for was the last one, and I think a lot of people there felt the same way. #womensrightsarehumanright

3. People have asked me many times, before the March and since, “What do I think this big protest is going to accomplish?” It’s a valid question. Protests mean nothing, without meaningful action afterwards. What I hope, and what think I already see happening, is that the March is beginning to engage people, many of whom never engaged before, myself included, in civic action and respectful discourse on very complicated and divisive issues on a greater level than we’ve seen in my ENTIRE lifetime. Whether you marched or not, whatever your reasons for marching or not marching, I think we can ALL agree that there are too many people in this country who are hurting, who need help, who need protection–civil rights protection, economic protection, health care protection, racial justice protection, environmental protection–our country is IN TROUBLE, and it was before Trump, before Obama, before Clinton, before Bush–these problems have deep, thorny roots. If Trump has done anything, it’s to turn over the foul, grimy complacent layer of dirt on them and expose to all of us just how ugly and deep they run.

It’s insidiously easy to sit back and let the government do whatever the government wants to do, easy to feel like you, one person, you’re not enough to effect change. If all we do is march, if all we do is talk and post, then you are absolutely right: The March was for nothing, and we are not enough, will never BE enough. But if, instead, the March, whether you participated in it or not, causes us to LISTEN to each other; to actively seek out opposing viewpoints and try to engage with the people who hold them in a respectful, positive spirit of mutual cooperation and compromise; causes us to actively seek out unbiased, unfiltered primary sources of information, like CSPAN, or, even better, to attend hearings and protests and meetings IN PERSON, rather than to continue relying on someone else to regurgitate FOR you the information you use to make your judgments; causes us to CALL OUR GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVES AND HOLD THEM ACCOUNTABLE TO THEIR PROMISES TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE; causes us to become involved at a local level in helping others–food drives, volunteering at schools and shelters and for trash pickups, causes us to stop talking and start DOING; causes us to stop reacting from the gut to sensational and polarizing news bites and stop perpetuating the cycle of disinformation and distrust–IF, and it’s a big IF, I know, because it’s a lot to ask of each other, IF this is what the March accomplishes, then that is EVERYTHING I hoped it would do. We can do this, America. I believe in us. I believe in you.

My mother was a true badass.

the men’s

the men’sI never read it. Like many children do, I rebelled against my parent’s teachings. In my case, that meant soundly rejecting my mother’s fire-breathing, chest-thumping, who-needs-a-man brand of feminism. I realize now how that must’ve felt like a rejection of her, of all she was, and all she’d hoped for me. I wish I’d read it then.

Though the divorce made the early part of my life tougher (needing donations from the food pantry to get by that week; going to work at age fourteen, cleaning my mom’s friends’ homes for extra money; wearing hand-me-down clothes that my mom’s kind teacher friends brought for us in black garbage bags; having to choose between clean laundry or a shower because they both drained directly into the ground beneath our house and would flood the basement if you did both; graduating from college thousands of dollars in debt from my student loans), compared to millions of other people in this country, I would say that, on the whole, since then, I’ve had, by many folks’ objective benchmarks, a pretty great fucking life.

It wasn’t always easy, but after that initial rough start, my family and I have been blessed for decades with steady employment; nice, roomy houses in safe communities with good schools; outstanding corporate health benefits; and enough financial security to be able to absorb emergencies, save for our children’s college educations, and prepare ourselves for a comfortable retirement. We are, in fact, living the American dream.

If you didn’t know me and know what my childhood was like, you’d think I’d always lived this life overflowing with a disgusting amount of privilege. You’d think it’d be easy for me, then, to sit back and say, “Hey, our family’s good to go. Now we can relax. To hell with everybody else.”

But it’s not easy. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t look around me and remember where my life started, how hard my husband and I had to work to get to where we are today, not to mention how much support and downright luck we’ve enjoyed along the way. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t feel an obligation to pay that forward, in any way I can, to people who have never, in their wildest dreams, had a single day as easy as one of my hardest ones.

Yes, I’ve had a great fucking life. But for all those out there who life is just fucking—the jobless; the homeless; those lacking a decent education to prepare them for changing workforce needs, safe neighborhoods in which to live, or affordable access to quality medical care; those suffering discrimination, denial of civil rights, or outright persecution because of their race, religion, gender, country of origin, or sexual orientation—

I see you.

I hear you.

I want to help you.

My badass mother did not live to see me become a mother myself; she died before my daughter was born. But where I may not have been my mother’s idea of a woman who runs with the wolves, my daughter, however, was born howling.

My badass mother did not live to see me become a mother myself; she died before my daughter was born. But where I may not have been my mother’s idea of a woman who runs with the wolves, my daughter, however, was born howling.

From her earliest days, when her first word was “no” and she refused to wear pink or sing the alphabet song on command or stop biting her little brother on the ass, she showed herself to be a proper little savage, full of spirit and fire and fight, a spirit we never, ever tried to squelch.

She has, in fact, been raised as a child of great privilege, but she has not been raised to be blind to injustice and suffering. On the contrary: as she has grown and matured and learned about the world around her, she has begun bringing her spirit of fire and fight to bear on those injustices she sees around her, the large and the small, learning to stand up and speak her mind, to channel her passions and energies into pushing back, hard, at bullies and bigots.

But speaking up alone isn’t enough, clearly. I have occasionally sensed in her, over the last couple of years, a hint of frustration with her too-submissive, too-conventional mother, a hint of sadness, even, that I seemed (at least in her mind) content to just keep baking cookies and writing my books and cleaning the bathrooms and doing the grocery shopping. Didn’t I want to do something more?

My girl—she wants to run with the wolves, and I know that she wants me to run with them, too. Her grandmother would’ve loved that.

So we will march this weekend, howling together at the top of our lungs.

We will march for our past—for her grandmother, my mother, who was a total badass right to her last breath.

We will march for our present—for the life of privilege and access that is in such stark contrast to the lives so many of our fellow citizens are living today, the life that COMPELS us, that REQUIRES us, to find ways to help and protect others.

And, because I know I will not live forever, we will march together for the future I want to see for her: a future where she, personally, not only has the freedom to do anything with her life that she wants to, but also a future where she and all her fellow Americans can live together in peace, in freedom, with equal opportunities for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, no matter their race, religion, gender, ethnicity, or orientation.

We can do better for each other, and we must.

This is #why I march.

Narya Marcille