You may notice my ring—the chunky, silver peace symbol against a field of black I often wear on my right ring finger—and, given today’s climate, you may think you know something about me. Once, its symbolism may have conjured thoughts of “hippies” or “peaceniks,” but today, more likely, it conjures an image of a “snowflake,” or perhaps even a “libtard.” Maybe you look at my ring and think, “What a liberal, running out and buying a peace ring, of all things. Hippy freak.”

You may notice my ring—the chunky, silver peace symbol against a field of black I often wear on my right ring finger—and, given today’s climate, you may think you know something about me. Once, its symbolism may have conjured thoughts of “hippies” or “peaceniks,” but today, more likely, it conjures an image of a “snowflake,” or perhaps even a “libtard.” Maybe you look at my ring and think, “What a liberal, running out and buying a peace ring, of all things. Hippy freak.”

Well, as they often are, looks can be deceiving. You see, this ring I wear so often, it’s not even mine—well, it wasn’t originally. I inherited it from my mother, when she passed away in 1996. Was she a hippy or a peacenik in her day? Probably so—I mean, the ring was originally hers, after all, and she was a raging liberal in her later years. She had it for a very long time, as evidenced by family pictures that have come to mean so much to me now, twenty years after her death; so yes, it’s likely she was an original hippy freak.

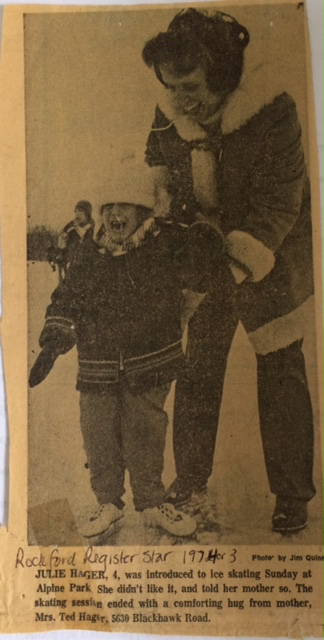

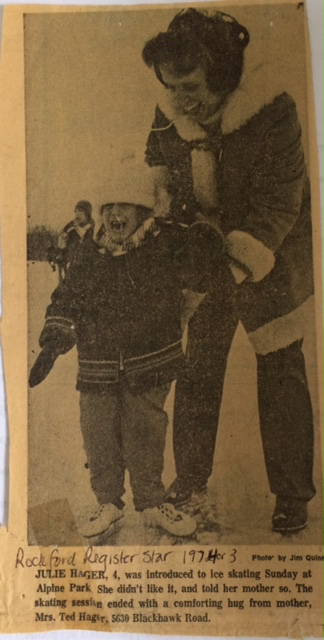

The first picture in which the ring appears made us both “famous,” at least in our local community. I was four years old, and Mom had decided to take me ice skating for the first time. As you can see from the image, it was not something I took to willingly. A photographer for our local newspaper, The Rockford Register Star, saw my mother smiling and laughing, and me, wailing and fussing, and thought it was a cute human interest pic (sadist).

community. I was four years old, and Mom had decided to take me ice skating for the first time. As you can see from the image, it was not something I took to willingly. A photographer for our local newspaper, The Rockford Register Star, saw my mother smiling and laughing, and me, wailing and fussing, and thought it was a cute human interest pic (sadist).

Notice the ring. More than forty years have passed since that picture was taken, and the hand wearing that ring is long gone, but still, sometimes, when I look at her ring on my finger now, I can almost feel her hands holding me.

She died before any of my children were born, and that was a source of great pain for me in those early years of motherhood. I longed to have the support and advice and connection with her and my children that most of my friends enjoyed with their mothers, who were all still living. That my kids would grow up never knowing who she had been hurt me terribly, and so began my perpetual campaign to teach them all about her, to let them know her through me.

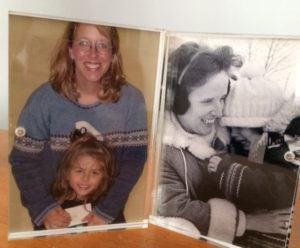

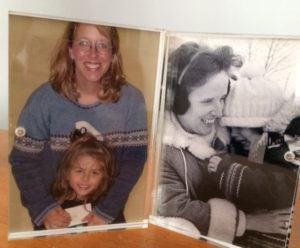

Sometime early in my daughter’s life, I decided that I wanted to recreate the ice skating picture with her that I’d had with my mother (hopefully with a bit less trauma), so when she turned 4, we headed to the skating rink for her first time. I asked my husband to take a picture of us.

Notice the ring on my finger (and notice the smile on her face, so unlike her mother). On my dresser now, years later, the pictures, one of me and my mother and her ring, and the other of me and my daughter and the same ring, are a concrete, tangible link from one precious life, one precious love, to the other.

Notice the ring on my finger (and notice the smile on her face, so unlike her mother). On my dresser now, years later, the pictures, one of me and my mother and her ring, and the other of me and my daughter and the same ring, are a concrete, tangible link from one precious life, one precious love, to the other.

I wanted to repeat the experience with my older son when he turned four, but we could never get him to be still on dry land, let alone on ice. We didn’t make it to the ice rink with him until he was around seven, and although I made sure to wear my mother’s ring and forego a glove on that hand, the opportunity for a picture never arose. But I know it happened, and I know that each time I reached down and helped my son back to his feet, I saw the ring on my hand, and felt my mother there with us.

When my youngest son turned four, he desperately wanted skating lessons, so I willingly obliged. This time, it was just the two of us at the rink. He was so excited and happy to be on the ice that I didn’t want to stop him with a picture; I let him zip around to his heart’s content, and in the joy of watching him, I completely forgot. It wasn’t until our next lesson that I remembered and asked another mom in the group to take a picture when the lesson ended.

Notice the ring.

Look through our family pictures for the last two decades, and you will likely see that ring on my hand in most of them. I have other rings, prettier, daintier rings, of course; beautiful, delicate confections that my husband has lovingly chosen for me. When I dress up for date night or a wedding or what have you, I choose one of those, and my mother’s ring stays at home on my ring stand. But still, most ordinary days, my mother’s big, solid, chunky peace symbol winds up on my finger. Its weight grounds me somehow; the knowledge that she walked this earth with it wrapped around her own finger makes me feel she is nearby, no matter where I am. Wearing it brings me peace and comfort and often, fortitude, in difficult situations.

I wish I’d had a camera with me last week, when we traveled to the Virgin Islands on spring break with our kids. As I always do, I wore my mother’s ring during the flights, which are difficult for me, and though I wasn’t planning on doing so, I slipped the ring on as we left to go snorkeling for the first time.

I was terrified. Something about no bottom I could touch with my feet, no poolside I could grab with my hands, filled me with silly horror. But my youngest son wanted to swim with the sea turtles, so there I was, taking a catamaran to Turtle Cove, quaking in my life vest and flippers. I rubbed my mother’s ring repeatedly, looking for calm and trying not to cry as I climbed down the ladder. I so wanted to do this for my two sons and my husband, to not let being afraid stop me from living.

Credit: https://www.emaze.com/@ACWZWWRO/Presentation-Name

After a few minutes in the water (and with the help of a pink pool noodle one of our guides tossed me), I began to relax. Then came the moment when our guide told us to look down, there were turtles right below us. I stuck my face in the water and searched all around beneath me—there. There they were. Two enormous turtles, gliding ever so slowly across the bottom. As I waved my hands gently in front of me to keep myself from drifting away from them, a flash of silvery light caught my eye. It was my mother’s ring.

I remembered, then, how when my siblings and I were kids, she had told us she’d always wanted to be a marine biologist (she became an English teacher instead, better with words than with math). I remembered, also, taking her to the dolphin show at the zoo the summer before she died, and how tightly she’d gripped my hand when the dolphin leaped above the water’s surface. I remembered her trembling at their power and beauty, remember how her eyes shone as she looked at me and squeezed my hand even tighter.

She would’ve loved this, I thought as I floated above the turtles. How I wish she could be here.

Then I remembered—she was.

I looked down at the turtles beneath me and went completely still. I moved my hand, moved my mother’s ring, before my face, so that it looked as if my hand were touching the turtles’ shells, as if, linked by her silvery ring, our hands, together, were gliding across their backs.

As I write this now, the only piece of jewelry I’m wearing is her ring. When I hit the Enter key or move the mouse, the ring glints in the morning light coming through my office window.

Notice my ring. Yes, it’s a peace symbol, a call sign for hippies, peaceniks, and snowflakes alike. Yes, it’s big and it’s clunky, not delicate or expensive or particularly feminine. But for me, wearing my mother’s ring has never been about what’s on the outside—it’s always been about all that it has held inside.

Notice my ring. Yes, it’s a peace symbol, a call sign for hippies, peaceniks, and snowflakes alike. Yes, it’s big and it’s clunky, not delicate or expensive or particularly feminine. But for me, wearing my mother’s ring has never been about what’s on the outside—it’s always been about all that it has held inside.

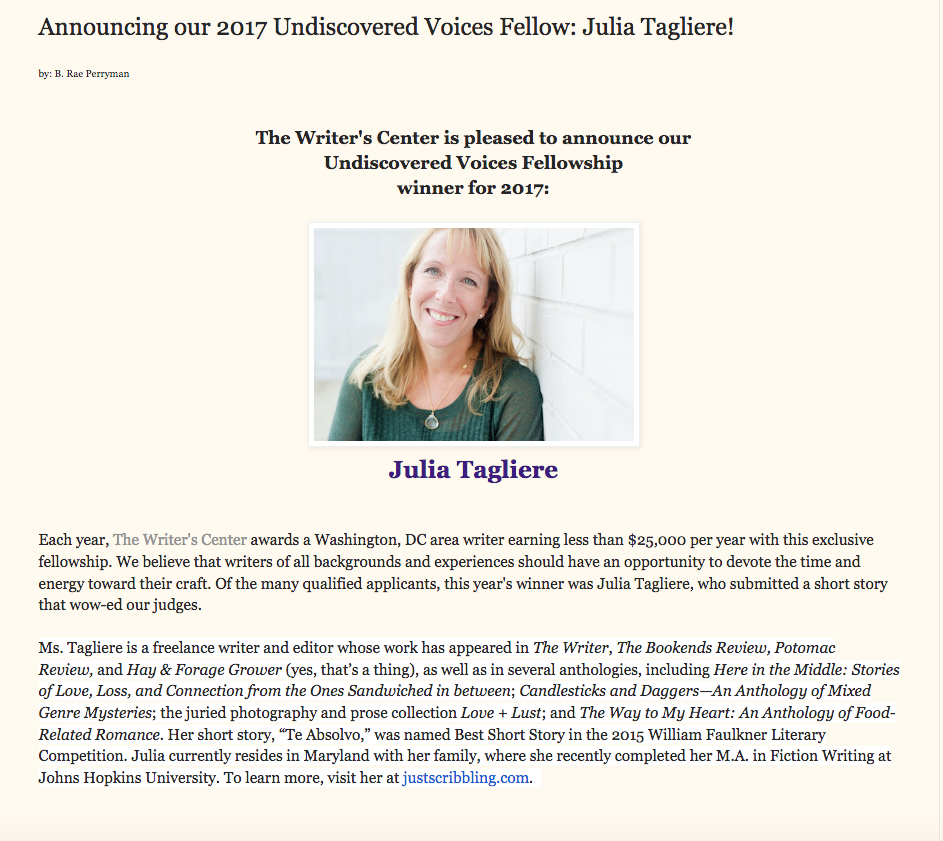

Sending out a brief message of heartfelt gratitude today to

Sending out a brief message of heartfelt gratitude today to  You may notice my ring—the chunky, silver peace symbol against a field of black I often wear on my right ring finger—and, given today’s climate, you may think you know something about me. Once, its symbolism may have conjured thoughts of “hippies” or “peaceniks,” but today, more likely, it conjures an image of a “snowflake,” or perhaps even a “libtard.” Maybe you look at my ring and think, “What a liberal, running out and buying a peace ring, of all things. Hippy freak.”

You may notice my ring—the chunky, silver peace symbol against a field of black I often wear on my right ring finger—and, given today’s climate, you may think you know something about me. Once, its symbolism may have conjured thoughts of “hippies” or “peaceniks,” but today, more likely, it conjures an image of a “snowflake,” or perhaps even a “libtard.” Maybe you look at my ring and think, “What a liberal, running out and buying a peace ring, of all things. Hippy freak.” community. I was four years old, and Mom had decided to take me ice skating for the first time. As you can see from the image, it was not something I took to willingly. A photographer for our local newspaper, The Rockford Register Star, saw my mother smiling and laughing, and me, wailing and fussing, and thought it was a cute human interest pic (sadist).

community. I was four years old, and Mom had decided to take me ice skating for the first time. As you can see from the image, it was not something I took to willingly. A photographer for our local newspaper, The Rockford Register Star, saw my mother smiling and laughing, and me, wailing and fussing, and thought it was a cute human interest pic (sadist).

Notice the ring on my finger (and notice the smile on her face, so unlike her mother). On my dresser now, years later, the pictures, one of me and my mother and her ring, and the other of me and my daughter and the same ring, are a concrete, tangible link from one precious life, one precious love, to the other.

Notice the ring on my finger (and notice the smile on her face, so unlike her mother). On my dresser now, years later, the pictures, one of me and my mother and her ring, and the other of me and my daughter and the same ring, are a concrete, tangible link from one precious life, one precious love, to the other.

Notice my ring. Yes, it’s a peace symbol, a call sign for hippies, peaceniks, and snowflakes alike. Yes, it’s big and it’s clunky, not delicate or expensive or particularly feminine. But for me, wearing my mother’s ring has never been about what’s on the outside—it’s always been about all that it has held inside.

Notice my ring. Yes, it’s a peace symbol, a call sign for hippies, peaceniks, and snowflakes alike. Yes, it’s big and it’s clunky, not delicate or expensive or particularly feminine. But for me, wearing my mother’s ring has never been about what’s on the outside—it’s always been about all that it has held inside. Wonderful podcast interview with WCCO’s Jordana Green and award-winning columnist and speaker

Wonderful podcast interview with WCCO’s Jordana Green and award-winning columnist and speaker  This post is part of the Candlesticks and Daggers Interview Series run by contributor Sati Benes Chock, and originally appeared January 19, 2017, on the blog of Candlesticks and Daggers editor,

This post is part of the Candlesticks and Daggers Interview Series run by contributor Sati Benes Chock, and originally appeared January 19, 2017, on the blog of Candlesticks and Daggers editor,